I have a daily meditation practice. For more than 10 years I took a correspondence course whose effect was a kind of meditation, and last year, I decided, since I have all the lessons, to restart at the beginning and go at my own speed. The lessons were written in the 1980s and '90s by a now-deceased Siddha Yoga teacher, and they are timeless. Sometimes I'll stay for days on one sentence that evokes an aha. Sometimes the lessons say things that poke me, and I've learned to accept the gift of that—to start at the point of poking and contemplate what's bothering me and follow wherever it leads … to a denied thought, to greater awareness and self-responsibility.

The lesson I've been on for a couple of weeks has a lot of pokes, one of which is eschewing the whole notion of diversity: It doesn't exist, because the Self (the Great Emptiness that a lot of people call God) that embodies us is everything and everyone.

I believe that is true. So it occurs to me that today's maligned effort to increase diversity is a way to reverse-engineer us back to the Self. The more diversity we are exposed to and metabolize, the more we experience who we really are.

For this reason, EVERYBODY's story is important for EVERYBODY.

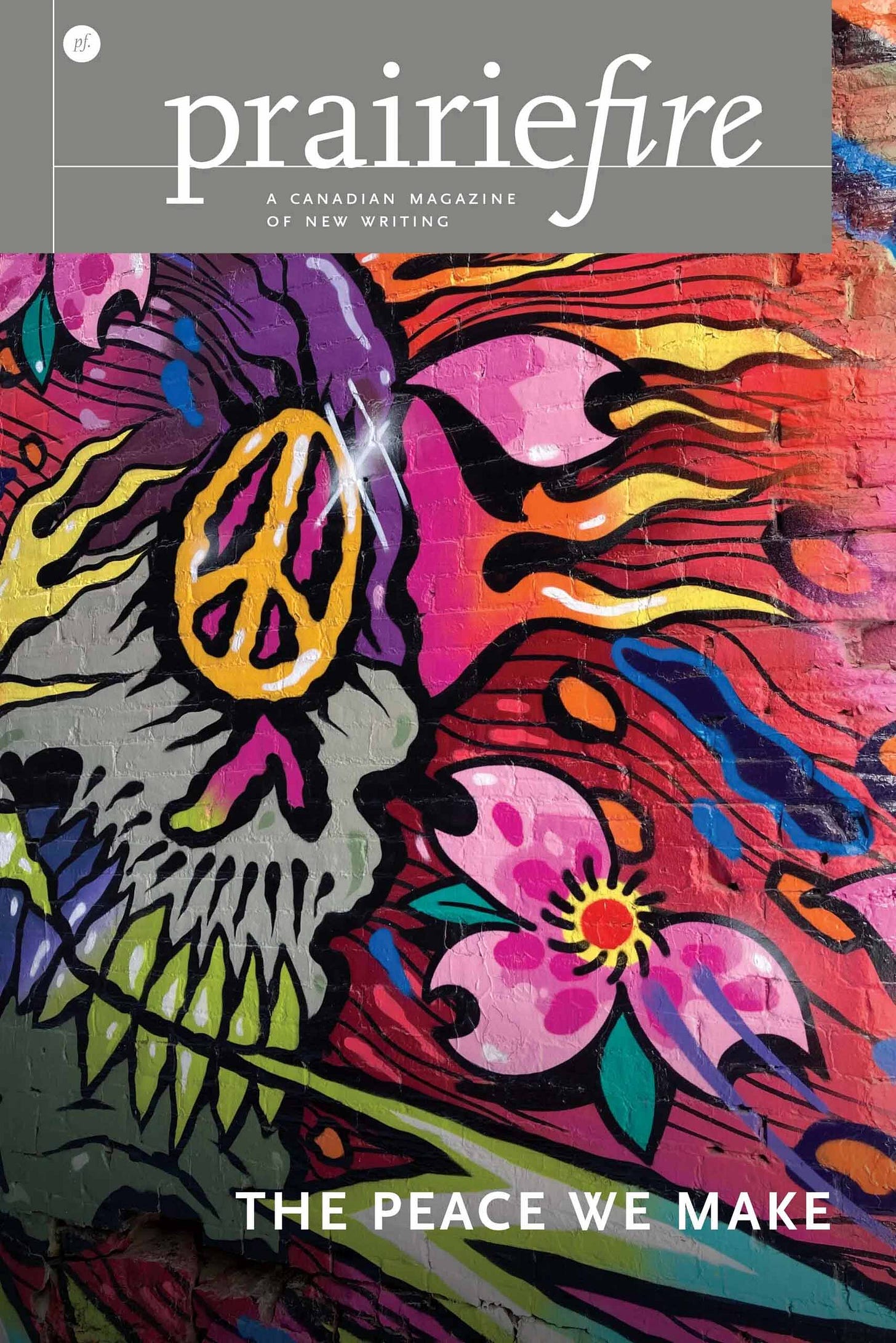

Two books inspired me to write the following essay, published in Prairie Fire (April 2023): the structure of Maggie O'Farrell's memoir I Am, I Am, I Am and the message at the end of Michelle Obama's memoir Becoming; she writes, if you don't see your own story in your culture, tell it.

Here's my thread to add to the diversity weave.

Walking Alone—Dangerous or Heroic?

Betsy Robinson

1.

I am naked, splashing happily in the big white porcelain tub in the little downstairs bathroom with the big red door that locks. I like that it locks, but at age four, I’m not savvy enough to twist the key. As soon as I am smart enough, I will hibernate in this room for hours—no matter how many times my younger brother and older sister pound on the door. But right now I am naked, splashing, and blissfully alone because Mom left me here and is somewhere else. I don’t like long baths, so when the voice in my curly brown-haired head booms “Enough!” I simply stand, grasp onto the side of the tub as I straddle it and climb out—a four-year-old’s version of vaulting the barrier. I don’t bother drying off. The big red door is open so I walk out . . . through the adjoining playroom with the cork floor, past the sliding concealed door into the dining room where I half-crawl up two carpeted steps to the front door which is always unlocked because that’s how it is in our little enclave of New York suburbia in 1955, and out the screen door I go.

I like how smooth and warm the white-veined blue slabs of marble on the front path feel on my little fat feet. The gravel on the driveway hurts, but I put each foot down carefully with as little weight as possible until I get to the paved road. We live on a dead-end street and our house marks the curve at the bottom of the first hill. If I go right, the road is flat, then descends in a second hill, and if I don’t make the next turn to the dead end, I might end up in the Hudson River. If I go straight up the first hill, I’ll get to where the cars go somewhere and that seems to me like a good thing to do.

2.

It’s 1969, and I’m walking down Bennington Drive, Bennington College, Bennington, Vermont, to the shrink, when a car pulls over. “Do you want a ride?” offers the driver. I’m unaccountably confused. I don’t want a ride, but I don’t want to be rude, and that’s when I see the penis. “Leave!” booms the voice in my head, and I veer off road into a thicket, down a bank of shrubbery and trees where I crouch and wait. After the car leaves, I climb to the top of the bank and resume my downhill walk—only to have another car pull over, but before he can say anything, I’m into the thicket again, shaking now. What is going on? This has never happened to me before. Men don’t look at me, let alone stop. I’m overweight and unattractive. Again, I wait for the car to leave, then climb back up to the road and complete the five-mile walk to the shrink. “What was the problem?” he asks as we begin my session. “I stopped to offer you a ride and you disappeared.”

3.

I’m in Epidaurus, Greece, home of the most ancient theater in the world. I’m traveling around Europe alone, after splitting off from some American and British friends. Sometimes I take trains, other times I walk. I’m living off the tuition money I saved for the college I’m not going back to. It’s approximately 4 a.m. on a blistering summer day in 1972 and I’m walking up a long country road in dark so devoid of illumination that I cannot see my hand in front of my face. I follow the edge of the road with my anemic flashlight, heading for a bus that leaves only once a day at 7 a.m. for Athens—my connection to the rest of my life adventure. Last night I saw a bad bus & truck musical in an amphitheater where, more than two thousand years ago, audiences of 13,000 Greek townspeople came to experience healing by watching music, singing, and dramatic games as ritual worship of Asclepius, the god of medicine. I am wondering what those people would think of the bad bus & truck chorus when I’m stabbed in my gut. I’d almost forgotten about this because it’s been several months. I’m pretty sure I’ve got a tampon in my knapsack, and as my groin gushes and I feel the wet, I do what I must do and veer off the road into the brush and trees. There are no fences. From the little I can detect, I’m in wild land. I pull off my shorts and underwear and am squatting half-naked behind a tree when I hear it: Hee-honh! Hee-honh! I’m going to be attacked by donkeys.

4.

Walking from the Ansonia Hotel on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, heading to my apartment where I am temporarily without a roommate, I am contemplating how nice it is to live alone. In my bulging shoulder bag I carry: the Con Edison cash from my former roommate who now lives in the Ansonia; my toe shoes from my dance class which I take because I am now a young New York actress and that’s what we do even though I have no intention of ever dancing on my toes which is way more painful than walking barefoot on gravel; there’s the jar of peanuts I just bought and know I shouldn’t eat if I want to keep off the weight I lost last summer; my journal crammed with entries about sex and longing and a couple of letters from my first ex-boyfriend with whom I finally lost my virginity; and my passport, still there from the trip to Europe almost two years ago. I’m feeling good. It’s nighttime and I like the dark, which is never as dark as a country road in Greece or Vermont. This is a great city. You are never alone, but still you can be by yourself and not talk to anybody if you don’t want to. At Broadway and Eighty-first Street, I turn right. My apartment is closer to Amsterdam Avenue, but I’m street smart and never walk there even in the daytime. As I approach my stoop, I pull out my keys. I walk up the two stairs, open the unlocked outer door, then as I’m unlocking the inner door, a man pushes past me into the vestibule. Something in my stomach does a nervous flip. “No,” says the voice in my head, but I ignore it. The man presses the elevator button, and when it comes, he turns back toward me holding the doors open with the openest, charmingest, toothiest grin I’ve ever seen. He is beautiful: the gleaming smile against his perfect brown skin is radiant. He looks like a model. I dismiss my stomach flip with white guilt. “Thank you,” I say, preceding him into the elevator. What a gentleman, I think as the doors close and he pulls out a knife.

5.

I am walking from a train station I’ve never been to before. I’m walking “home” to a house I’ve never lived in where my mother and youngest brother now reside while he finishes high school. There is no more cohesive family; my father is dead and we each—my other two siblings and I—have scattershot ourselves out into the world like sharp-edged shrapnel; I’m the only one who ever comes home and I make those trips as rarely as possible. “No ride necessary,” I’d told my mother. It’s late afternoon and I’m walking up a country road under a canopy of red and yellow and orange leaves because it will prolong my alone time before I enter the fug of dysfunction. No cars stop to offer me a ride, and I wouldn’t take one if they did. Nor would I run into the brush. I’m not scared or hyper-alert because I am confident. If someone stopped, I would simply say a polite but steely “No thank you” without eye contact; I don’t care what anyone might think.

Nothing happens on this walk and the trees smell sweet—the pungent aroma of decay. I am about twenty-five years old and I’m wearing clothes. My mother never approves of my wardrobe, but I don’t care. I will stay in her house, I will spend the night as I promised—unless it is too uncomfortable, in which case I will walk myself back to the train station no matter what the time. Because I can. I am free. I travel alone.

6.

It’s 1986 and I’m walking up Ninth Avenue from a theater where I have just done the best work I am capable of—a one-woman play that I wrote and performed. The audiences laughed and loved it. I loved them. Although I’ve yet to have the conversations and rejections telling me that the work is never going to be commercially produced, somehow I know I am done with theater. I’ve walked to and from this and other theaters many times in the last decade, smelling the raw fruit in the open-air stands, sidestepping vagrants and piss, watching all the other pedestrians and wondering where they came from and where they are headed. And now, the voice in my head says, this chapter is over. As usual, it is right. And I set off on a curlicued path of self-discovery—more therapy, many jobs, self-awareness workshops, self-hating workshops, and onward. It is a solitary and extraordinarily interesting walk with no end.

7.

A vacuum. That’s the only way to describe the ride down in the elevator of Doctors Hospital on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It’s 1990. I am thirty-nine years old and I am carrying a bulky blue body bag. After the elevator hits Mezzanine, half-comatose, I find my way to the emergency exit and I’m about to step onto the street when a man in a uniform with an almost unintelligible accent accosts me. He is telling me I can’t leave with the bag and the more I resist, the more gentle he becomes with his gibberish, and the more enraged I am, until finally I shout, “My mother is dead and these are her things!” By the shopping bag he produces, I glean that the problem is the body bag, which I surrender to him in exchange for the new container for my mother’s ratty coat and street clothes because she is lying dead in the ICU and no longer needs them, and I am her next of kin, executrix, power of attorney representative, writing partner, and best friend. Although she lacked parenting skills, it turned out she was the world’s best adult friend, and our last decade more than made up for the violence, the drunkenness, and the rest of the mess. It’s a long story and not one I need to dwell on anymore. Suffice it to say that we finished off my childhood and moved on in tandem to a partnership based on humor and mutual acceptance of our differences. With the new shopping bag, I exit the building. It is 11 p.m. Mom died at 10:10. I grab a cab. When I get home, I throw out the entire contents of the bag.

8.

As you probably deduced, I survived my naked four-year-old’s walk. As I reached the apex of the hill, Mrs. Askew who lived in the corner house spotted me and phoned my mother, who galloped up the hill like a maniac, catching me as I made my way down busy Long Hill Road. “What are you doing?!” she wailed, wrapping me in her arms and lugging me home. “I was taking a walk,” I answered, intrigued by her pounding heart which was under the illusion that I was alone.

When I was older—for instance in the Bennington shrink’s office—I experienced that pounding heart myself. When the shrink asked me what had happened, I explained, “A man doing this (I demonstrated) with his penis had just offered me a ride.” The shrink looked at me with a gaze that I can only describe as both incredulous and lecherous. “He was masturbating,” he announced. And as I blushed, his eyes turned from incredulous and lecherous to disgusted. “Don’t you know that men who do that aren’t going to hurt you?” Heart pounding, voice in my head booming, I staggered home from that session, but was so desperate, I kept going back.

The Greek donkeys didn’t attack me, and I made it to the bus depot in plenty of time to see the bus & truck actors arrive by car to take the same bus as me back to Athens. They looked bored. They were summer gigging and couldn’t have cared less whether they were doing it in a theater inhabited by ghosts from 400 B.C. The voice in my head had a good laugh.

The man in the elevator didn’t attack me either; he just stole everything I had and taught me always to listen to the whisper of the voice in my head—no matter how much white guilt or peer pressure or desperation and fear of being wrong might try to override it. If I make a mistake, I apologize. So far I have not made many serious mistakes and I have witnessed many times a look of befuddlement or rage on the faces of men of all races who have expected my denial to kick in, or on a group of faces in a homogeneous clan under the influence of groupthink. So far I have done many good deeds for strangers who could not hear their inner voices—by simply relaying what mine says: a warning, a compliment, a bit of comfort when it is needed. And then I walk on.

I go by foot in comfortable shoes and never naked. For decades I’ve walked all over Manhattan island—for auditions, then jobs, then the pure pleasure of adventure. There are no donkey fields to avoid and I no longer need tampons. No phone or camera either. I want to be where I am, seeing and hearing what is right in front of me.

Although some scary things have happened walking alone, rather than learn not to do it, I learned how to do it. Because in truth, we are all alone. I learned that watching my mother die. And simultaneously, we are never alone—says the voice in my head, the all-knowing wisdom borne in each of us that is my unconditional companion.

It’s funny: walking alone, being a loner—it’s judged both as aberrant or dangerous in communal society or, in the movies, courageous and heroic. In truth it’s neither of those things. It’s simply some people’s life plan due to the way they are made. We can spend our lives judging ourselves as deficient—for not forming families, having two million social media followers, and the like. Or we can be so curious about this unique journey that we are constantly in awe of what we see—about ourselves and our fellow travelers. I choose awe.

Betsy Robinson is a novelist, journalist, playwright, and editor. Her most recent novels are Cats on a Pole and The Spectators (Kano Press, 2024). They are sometimes funny loners' journeys. www.BetsyRobinson-writer.com.

“I choose awe.” ❤️